Subordinate clauses are clauses that don’t form a simple sentence on their own, and are connected to the main clause of a sentence. In a way, they’re like little kids. They can’t be left alone and, often, their words don’t really make sense. See for yourself:

Confused? That’s an appropriate response.

That confusion isn’t your fault—it’s just the nature of unaccompanied subordinate clauses. They contain subjects and verbs, but can’t stand on their own as complete sentences. They need help to express a complete thought. Until they get that help, these clauses won’t make much sense.

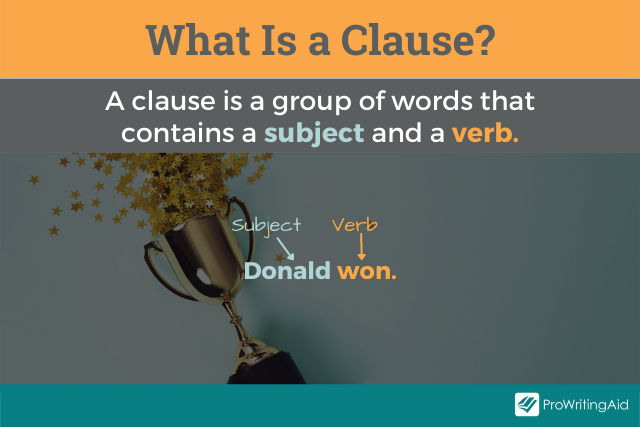

A clause is a group of words that contains a subject and a verb. There are two main categories of clauses.

You’ve already been introduced to the subordinate, also called dependent, clause. To have a full understanding of how dependent clauses work, it’s important to understand the other category: independent clauses.

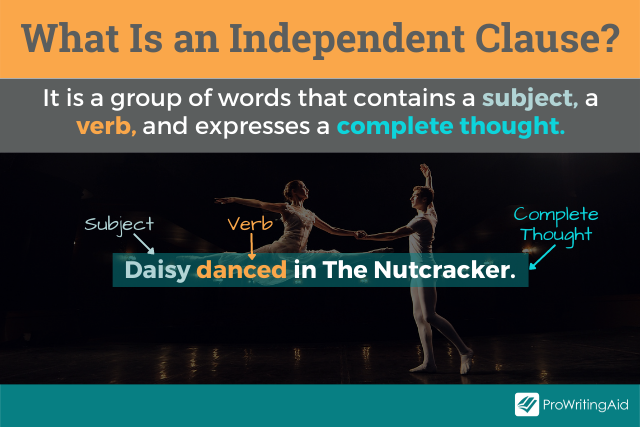

An independent clause can stand alone as a simple sentence. It expresses a complete thought. A dependent clause cannot.

An independent clause has three components:

In these examples, the subjects are bold, and the verbs are highlighted.

Poor Joe—but hey, applause to him for trying! And, his loss has allowed us to observe the three components of independent clauses. Take that win, Joe!

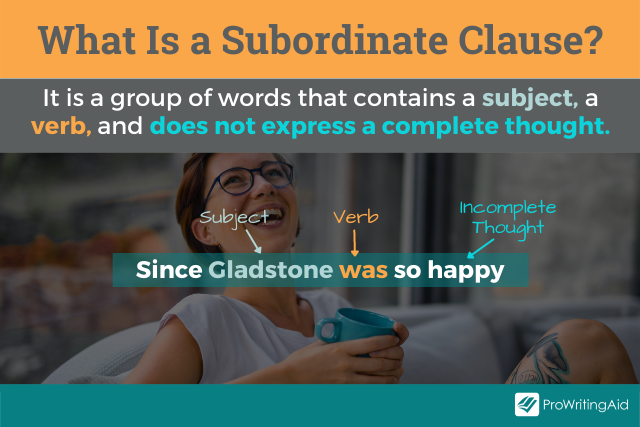

Subordinate, or dependent, clauses also contain a subject and verb, but they do not express a complete thought. They cannot stand alone as sentences. Dependent clauses can only exist in complete sentences when connected to an independent clause.

Let’s revisit those dependent clauses, in bold, from the opening of the post. This time, we’ll connect them with independent clauses and clear up the confusion they left us with.

See that? With a little hand-holding from independent clauses, the subordinate clause makes sense. It does its job, which is to add information to the independent clause. The dependent clause can’t stand by itself, but it does add meaning to a sentence.

There are three types of subordinate clauses: adverb, noun, and adjective.

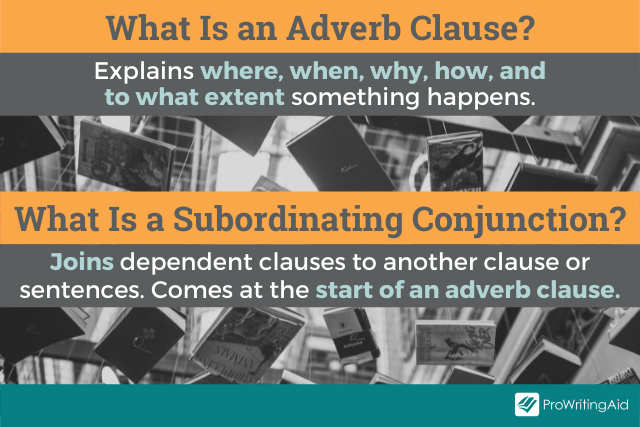

Predictably, adverb clauses function as adverbs; they explain where, when, why, how, and to what extent, and modify verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs.

Adverb clauses begin with subordinating conjunctions, which are words that link dependent and independent clauses by establishing a relationship between the two clauses. The relationship can be based on time or place, condition, concession, cause/effect, and comparison/contrast.

Some common subordinating conjunctions are because, since, if, whenever, even if, until, while, as long as, and though.

The earlier examples of subordinate clauses, the ones about the monster situation, are adverb clauses; these adverb clauses answer “why?”

In those examples, the dependent clause comes before the independent clause, so a comma is required after the dependent clause.

Here are a few more examples of subordinate adverb clauses. In these, the independent clause comes first, so no comma is required.

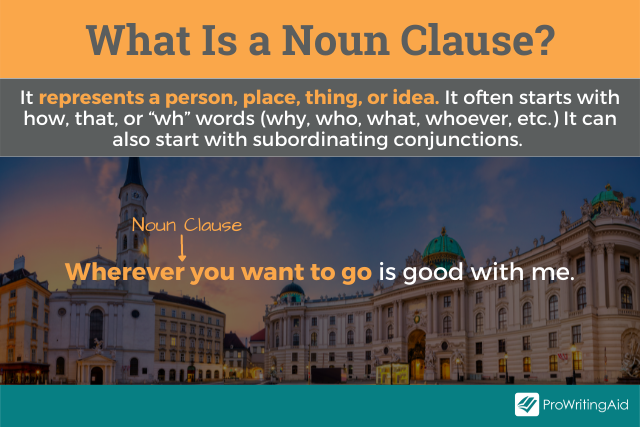

Noun clauses function as nouns, representing a person, place, thing, or idea. Noun clauses often start with how, that, or wh- words (why, who, what, whoever, etc.) They can also start with subordinating conjunctions. Noun clauses aren’t set off from the sentence with commas. For example:

Wherever you want to eat is fine with me.

In this example, “wherever you want to eat” is the subject of the sentence; it’s a noun clause representing a place.

It could be swapped out for an actual place: “Village Pizzeria is fine with me.”

Here are a few more examples of noun clauses:

You can probably guess that adjective clauses function as adjectives. They modify nouns or pronouns and answer “which one?” or “what kind?”

Adjective clauses are also called relative clauses since they usually start with a relative pronoun. Examples of relative pronouns include that, where, when, who, whom, whose, which, and why.

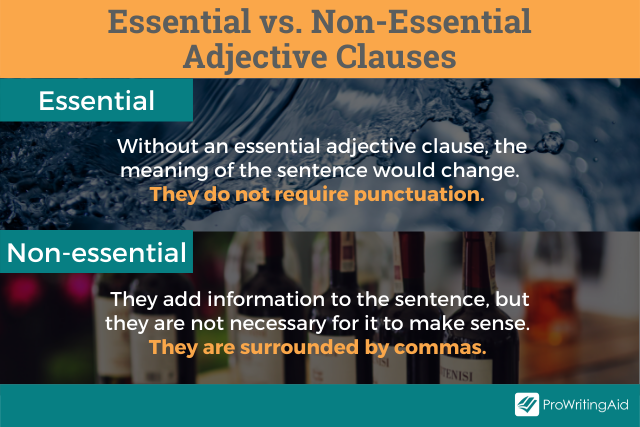

Some adjective clauses are an essential, or necessary, part of a sentence. Without them, the meaning of the sentence would change. For essential clauses, no punctuation is required. For example:

If you removed the relative clauses, the meanings of their respective sentences could be unclear or would change entirely.

In the first example, the adjective clause that we picked the other day identifies which peaches the speaker is talking about. If “we” had picked some peaches and bought others from the store, that clause is essential for identifying which peaches have gone bad.

In the second example, removing the clause would leave the sentence like this: “I don’t like people.” But that’s a distortion of the speaker’s meaning. Therefore, the adjective clause is essential for conveying the sentence’s actual meaning.

Non-essential adjective clauses simply add information about the noun they modify, but their presence or absence does not change the meaning of the sentence. Non-essential clauses provide extra, but not absolutely necessary, information, and are surrounded with commas. For example:

In the first example, the point is that the student missed the exam. In the second, the point is that the wine is delicious. The subordinate clauses in each sentence simply provide additional information about the student and the wine, respectively.

FYI: Essential and non-essential clauses are also called restrictive or non-restrictive clauses.

Subordinate clauses provide opportunities to add variety to your sentence structure, and variety makes your writing more interesting, engaging, and sophisticated overall.

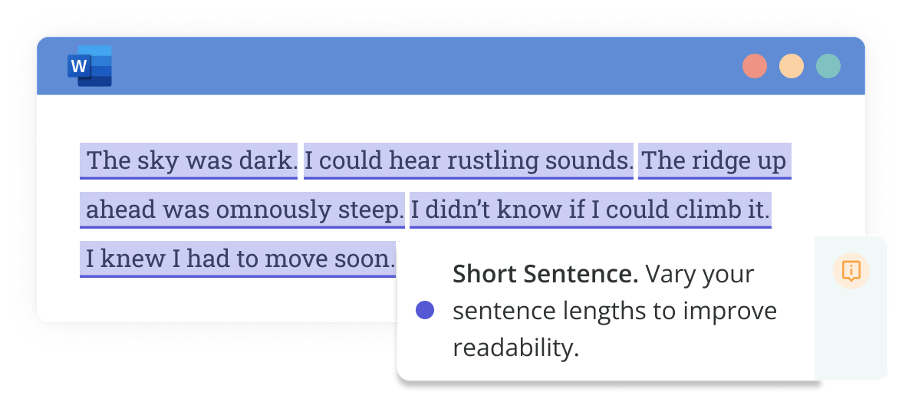

ProWritingAid’s Sentence Length Report shows you your sentence length variety across your document. This gives you valuable clues as to which sentence type you use most often; simple, compound, or complex.

Writing that uses the same sentence structure repeatedly can get dull very quickly. And you don't want your readers falling asleep!

This allows you to see where you may have used too many similar sentence starts and sentence structures.

But how do you fix poor variety? Thankfully, subordinate clauses can help. You can connect subordinate clauses to independent clauses in different ways to create complex or compound-complex sentences.

To create a complex sentence, connect a dependent clause (or more than one) to an independent clause. Here are a couple of examples:

To create a compound-complex sentence, connect a subordinate clause (or more than one) to two (or more) independent clauses. For example:

Subordinate clauses may be problematic when left on their own, but with an independent clause to help them stand, they bring interest, variety, and creativity to your work. Use them well!

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.