How did the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act change business taxes?

The Tax Cut and Jobs Act made significant changes to the corporate income tax and taxes on pass-through businesses. While the individual income tax provisions and pass-through provisions expire after 2025, many of the other business tax provisions are permanent.

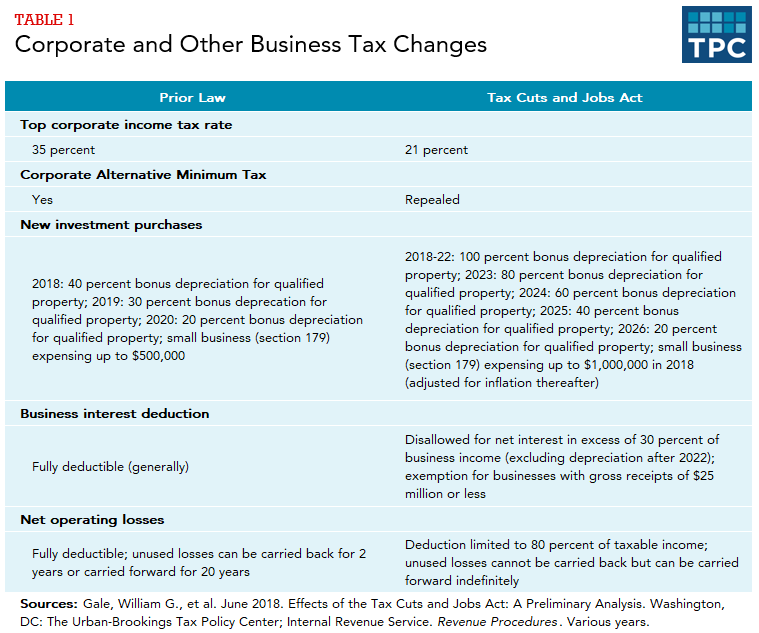

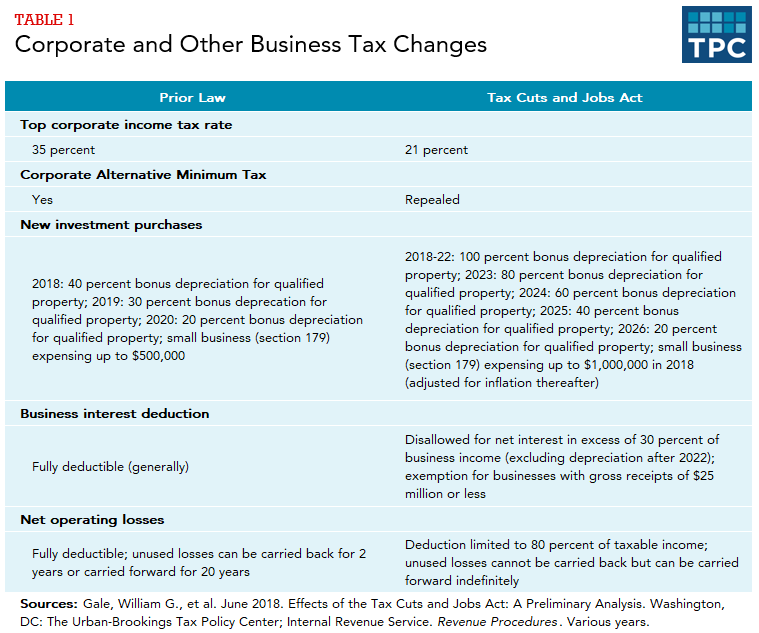

The Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA) reduced the federal top corporate income tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, bringing the combined US federal and state rates to about the average for most other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, and eliminated the graduated corporate rate schedule (table 1). TCJA also repealed the corporate alternative minimum tax.

TCJA allowed businesses to deduct the full cost of qualified new investments in the year those investments are made (referred to as 100 percent bonus depreciation or “full expensing”) for five years. Bonus depreciation then phases down in 20 percentage point increments beginning in 2023 and is fully eliminated after 2026. Prior law allowed 50 percent bonus depreciation in 2017, decreasing the percentage in subsequent years and fully eliminating it after 2020.

TCJA doubled the Section 179 expensing limit for investments by small businesses from $500,000 to $1,000,000 in 2018 (adjusted for inflation thereafter) for qualified property (sometimes called “small business expensing”). It also simplified accounting rules for smaller firms.

To offset the cost of the tax cuts, TCJA limited the amount of net business interest (interest paid less interest received) that businesses can deduct to 30 percent of business income before interest, depreciation, and amortization. Starting in 2022, the adjustment for amortization and depreciation was removed from the limitation, making the cap more restrictive. Businesses with gross receipts below $25 million are exempt from the limitation. Previously, interest paid was generally fully deductible in computing taxable income for all businesses.

TCJA limited the deduction for net operating losses to 80 percent of taxable income. It also repealed carrybacks of losses, except for certain businesses, but allows taxpayers to carry forward losses indefinitely. Under prior law, net operating losses could offset 100 percent of taxable income, and businesses could either carry back unused losses for two years or carry them forward for 20 years.

The new law also eliminated the domestic production activities deduction (Section 199) and modified other smaller provisions such as the orphan drug credit (an incentive for creating drugs for rare diseases), the deduction for Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation premiums, and the computations for life insurance reserves. In addition, starting In 2022, expenditures for research and experimentation are to be amortized over five years (15 years for offshore research and experimentation expenses), instead of being immediately deductible.

Unlike C-corporations, pass-through firms such as sole proprietorships, partnerships, and S-corporations are not subject to the corporate income tax. Instead, the owners include their share of profits as taxable income under the individual income tax.

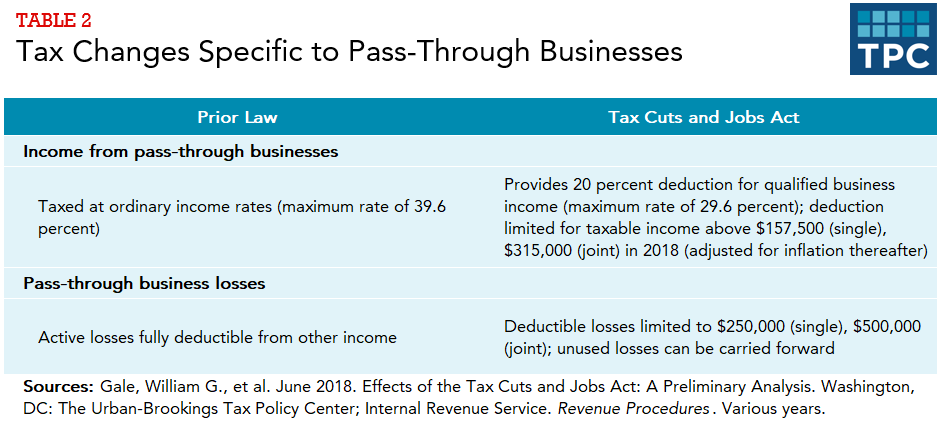

In general, TCJA’s changes to the business income tax base, including the limits on interest deductions and net operating losses, apply to pass-through businesses as well as C-corporations. However, the TCJA also included changes specific to pass-through businesses (table 2). Those are scheduled to expire after 2025 along with other individual income tax changes implemented by the TCJA.

The deduction for pass-through businesses allows all joint tax filers with taxable income below $315,000 ($157,500 for single filers) in 2018 to deduct 20 percent of their qualified business income (QBI). The income amounts are adjusted for inflation each year: for tax year 2024, they are $383,900/$191,950. The 20 percent deduction lowers the effective top individual income tax rate on business income from 37 to 29.6 percent.

If taxable income exceeds those thresholds, the deduction can be reduced depending upon the type of business, the wages paid, and the investment property owned by the business. For personal service businesses (such as law firms, medical practices, consulting firms, or professional athletes), QBI phases down on a pro rata basis. For tax year 2024, once taxable income reaches $483,900 for joint filers ($241,950 for other filers), QBI is zero and there is no longer any deduction.

For all pass-through businesses, whether they are personal service firms or not, an additional two-part formula limits the deduction once taxable income exceeds the $383,900/$191,950 thresholds for tax year 2024. Under the formula, the deduction is limited to the greater of either 50 percent of the wages the business pays its employees or 25 percent of wages plus 2.5 percent of the basis of the business’ qualified property. Business owners compare those calculations to 20 percent of their QBI and may deduct only the smaller amount. The limit on the deduction phases in over the same income range as above.

A major advantage of organizing as a pass-through business rather than as a C-corporation is that pass-through business owners can use business losses to offset taxable income from other sources. TCJA limits the amount of active pass-through business losses that business owners can deduct against other income to $500,000 for joint filers ($250,000 for other filers). Unused losses, however, can be carried forward and used in future years (table 2).

TCJA made sweeping changes to the treatment of foreign source income and international financial flows. Under prior law, the US taxed the income of multinational firms on a worldwide basis, meaning that all income was taxed, regardless of where it was earned, less a credit for foreign taxes paid. However, the tax due on active foreign-source income of foreign subsidiaries of US multinationals was deferred until the income was made available to the US parent company.

The TCJA created a modified territorial tax system. US corporations continue to owe US taxes on the profits they earn domestically. But TCJA exempted from taxation the dividends that domestic corporations receive from foreign corporations in which they own at least a 10 percent stake.

Under a pure territorial system, firms would have a strong incentive to shift real investment and reported income to low-tax jurisdictions overseas, while shifting deductions into the US. Several provisions were created as guardrails to reduce the extent to which companies take those actions.

The minimum tax on global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) imposed a 10.5 percent minimum tax, without deferral, on profits earned abroad that exceed a firm’s “normal” return (defined in the law as 10 percent of the adjusted basis in tangible property held abroad). Companies can use 80 percent of their foreign tax credits, calculated on a worldwide basis, to offset this minimum tax.

Whereas GILTI acts as a “stick” to prevent companies from making investments in intangible assets overseas, a deduction for foreign-derived intangible income (FDII) acts as a “carrot” to provide an incentive for firms to hold intangible assets in their US affiliates. FDII is income received from exporting products whose intangible assets are held in the United States. For example, a pharmaceutical company will be able to deduct some income from overseas drug sales if the patent on the drug is held in its US parent company.

TCJA also created a new base erosion and anti-abuse tax (BEAT), which—not surprisingly, given the acronym—is another “stick.” BEAT imposes a minimum tax on otherwise deductible payments between a US corporation and a related foreign subsidiary.

To transition to the new system, TCJA created a new deemed repatriation tax for previously accumulated and untaxed earnings of foreign subsidiaries of US firms equal to 15.5 percent for cash and 8 percent for illiquid assets. In 2015, it was estimated that US companies held more than $2.6 trillion in untaxed income in their foreign affiliates (Barthold 2016). Companies have eight years to pay the tax, with a back-loaded minimum payment schedule specified in the law.

As of 2023, Congress has discussed but not approved any changes to the scheduled corporate tax changes that helped lower the TCJA’s fiscal cost. In 2022, R&D deduction amortization and the more restrictive net-interest deduction cap went into place, while 100 percent bonus depreciation for capital investments began phasing down in 2023. In December 2022, TPC projected that restoring bonus depreciation, R&D expensing and the less restrictive net-interest deduction cap would cost about $480 billion over the next decade.